Latest Addition to the Theater

Our Art Gallery

| ||||

3420 CASS AVENUE MIDTOWN-DETROIT, MICHIGAN 48201

CINEMA GALLERY

www.CASSCITYCINEMA.com

CRUMB UNIVERSE

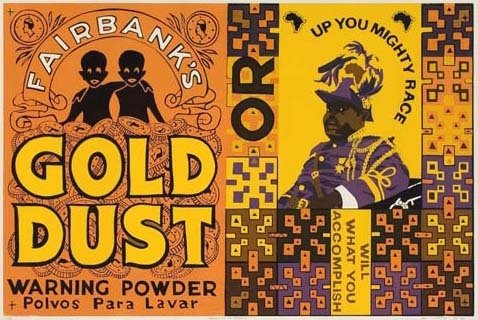

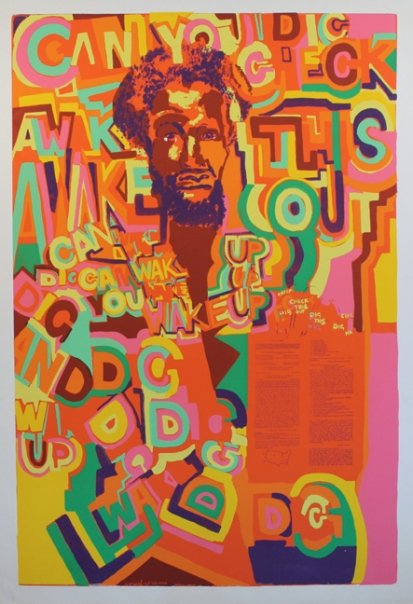

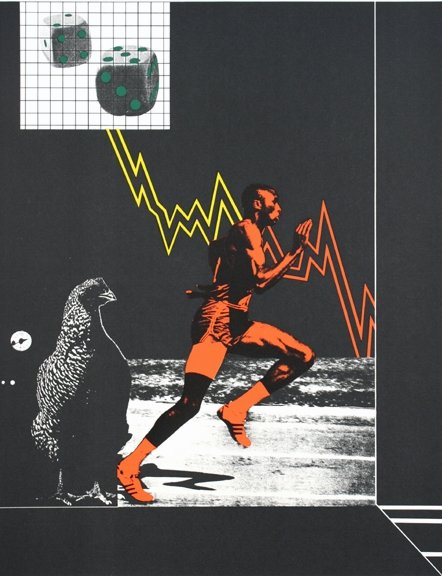

AfriCOBRA

AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) was an art collective formed in Chicago in 1968 by a group of African-American artists who were determined to address issues of Black liberation and self-determination in their work. Founding members including Jeff Donaldson, Barbara Jones-Hogu, Wadsworth Jarrell, Jae Jarrell and Gerald Williams who gathered regularly to craft a manifesto that laid out their goals of creating an “art for the people, not for critics.”

Opening February 9th, 2012, The Cinema Gallery at Cass City Cinema is proud to present the first Detroit exhibition of the original 1971 series of large screenprints that AfriCOBRA produced in order to help disseminate their pro-Black, positive images. Outside of museum collections including the Art Institute of Chicago, the DuSable Museum of African American History (Chicago), and the Smithsonian, few impressions of these powerful prints have survived. Included in the exhibition will be original prints created by different members of the group. These examples come from the large Azz-Lusenhop Black Arts Movement Collection and were exhibited in 2010 in an exhibition at Northwestern University outside of Chicago.

Wall Street Journal

December 1, 2012, 12:00 PM ET

Why It’s Better to Watch Movies in a Theater

COMMENTARY

By MARGARET TALBOT

One evening last week, I went to see “Lincoln” at a movie theater in a downtown San Francisco shopping mall. The theater’s message reminding you not to text and to turn off your cell phone was particularly thorough and Draconian (something about how the management would find you and would eject you), so when my own phone began bleating insistently just as the announcement finished, I was more than usually embarrassed. My scurry to the exit was a blushing perp walk, with several people on the aisle hissing and grumbling and one older lady overdoing it, I thought, by addressing me as “The Stupid Woman.”

But when I got back to my seat, and settled in with the rough-and-tumble politics of 1865, and the tender, craggy countenance of Daniel Day-Lewis’s Lincoln, I found myself feeling grateful. Sure, I could have done without the “Stupid Woman” comment. But I also felt, as I do increasingly in movie theaters, the pleasure and relief of knowing that for two-and-a-half hours, I would be permitted the grace of concentration. I would not be answering e-mail, or the phone, or gazing guilty over at a basket of laundry in need of folding or dog hair in need of vacuuming—the sorts of things I too often do when I’m watching a movie on TV or on a laptop at home. I would be given a reprieve from multitasking. And when I wept or laughed or gasped in dismay, I knew I would be doing it in the company of strangers who were there in that theater for the same purpose: To be transported by, immersed in, somebody else’s intricately realized vision of life.

That communion in the dark is an experience that many fewer of us are having in the age of home entertainment and instant downloads. In 2011, movie theater ticket sales fell to their lowest point since 1995, and took another dip this past summer, perhaps partly in response to the Colorado movie theater shootings. In 2002, the average moviegoer went to the theater eight times a year; last year it was 5.8 times. And the decline is most apparent among younger moviegoers. The only age groups that attended slightly more movies last year than the year before were the 40-49 year olds and the over 60’s.

Is it only muzzy-headed, middle-aged nostalgia that makes me think these numbers are pretty sad? The fact is I’m grateful to be able to watch movies on my laptop. My cineastic teenaged kids, who can download silent Swedish movies from the 20s, and pre-code gangster movies and just about anything else they might have read about and want to see are getting a deeper cinematic education than I ever had. I love that.

But I also know I’d never want to forgo the movie theater, the focus and the paradoxical intimacy of watching in a crowd. In the silent era, movie theaters were palaces: ornate and grand, Moorish and Chinese, vast and vaulting. They didn’t serve popcorn because popcorn was déclassé; it was what spectators munched at carnivals and circuses. In the 30s, movie theaters became smaller, more streamlined and democratic in design. There were fewer with different tiers of ticket prices, and the owners brought in snacks (the popcorn harvest in the U.S. took off.) That evolution would eventually bring us the shopping mall multiplex with its buckets of popcorn and super-sized soft drinks—a long, long way from the movie palaces. And yet even the boxy multiplexes offer a different experience from home viewing—one that’s even more of a refuge as our electronic distractions multiply and our attention spans shrink.

So, my apologies to my fellow spectators at that showing of “Lincoln” last week. I’ll be seeing it again with my kids when I get home to Washington, D.C. And this time, I’ll leave my phone at home.

Margaret Talbot, the daughter of Warner Bros. actor Lyle Talbot, is a staff writer at The New Yorker and the author of “The Entertainer: Movies, Magic, and My Father’s Twentieth Century.“

PAST EXHIBITONS